Porn Before It Was Chic: An Interview with Radley Metzger on Sex and Cinema

When master of erotic art cinema Radley Metzger takes the stage, you know you’re in for a treat. At the perfect age of eighty-five, the iconic filmmaker is every bit as charming, intelligent, gracious, charismatic, and wonderfully witty as ever, regaling us with tales of the ins and outs of his historic and tremendous career. It’s been thirty years since the release of his last film, The Princess and the Call Girl, but thanks to The Film Society of Lincoln Center and their “This is Softcore” series, audiences were able to get a taste of his stunning and progressive mid-career films, from the swinging sensation of Score to the deliciously strange The Lickerish Quartet.

Not only a filmmaker, but an editor and distributor as well, Metzger began his career as an editor at Janus Films, cutting trailers for the likes of Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman, after releasing his acclaimed but unsuccessful passion project Dark Odyssey and starting his own distribution company Audubon Films (named after the legendary Audubon Theater in Washington Heights). Debuting in the 1960s and ’70s, his films were lauded for their candidly sexual nature, garnering attention with an X-rating—but for Metzger, it’s always been the “in-betweens” that have mattered most. From his literary adaptions such as Therese and Isabelle, the black-and-white youthful lesbian love story with visuals akin to that of Alain Resnais, to his Henry Paris hardcore films like the hilarious and creamy dreams of The Opening of Misty Beethoven, his work is always as expertly crafted as it is erotic.

Having made films internationally for most of his career, Metzger’s devout professionalism and passion for storytelling and detail allowed him to call upon some of the most sought after set designers, composers, and directors of photography from around the world, resulting in work that is as modern and progressive in its sex positive attitude as it is aesthetically impeccable in its lavish grandeur.

I’d love to know more about your first theatergoing experiences at the Audubon Theater as a child. What films did you see there that informed you and made you want to go into cinema yourself?

When I came of age and was interested in film and theater, there were only two theaters playing foreign films in New York. One of them is the Thalia up by the symphony space, and the other was the Apollo on 42nd Street, before 42nd Street went to grind houses. And basically, with the exception of those two, you saw Hollywood films. Audubon Theater played Hollywood films, and the first film I ever saw, which was there, was the big MGM film called Manhattan Melodrama with Clark Gable. As time went on, if you really wanted to see something really exotic and unusual–I guess today it would be Andy Warhol–a foreign would be from England in English; subtitled films were very obscure. So you would flock to see something like Dead of Night or Brief Encounter, these were very much against the normal flow of Hollywood product.

But when I was a little guy, it was strictly Hollywood films. I was really lucky because they all talk about the Golden Age of Hollywood being 1939– Gone With the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, and so on. Well, in 1939 I was 10 years old, and you’re very special when you’e 10 years old. I think your receptors are highly-developed and you are able to absorb much more. As we get older we tend to lose that ability of complete absorption. So being able to see the Golden Age at the age of 10 was very special; I think people that weren’t 10 years old in 1939 should regret it. I stood on line for an hour to see The Wizard of Oz.

Can you tell me about your work at Janus Films as a trailer editor? You’ve mentioned L’Avventura as an important one, but are there any others you were particularly proud of?

They had Wild Strawberries coming up, but before that they took over a film from an exploitation distributor because Ingmar Bergman was really flogged around. They had one of his early films, which was actually three stories put together, and it was called Thirst. Well, no one would go to see a movie called Thirst, so this distributor called it Three Strange Loves. So Janus, when they were taking on Wild Strawberries (and I think they had Seventh Seal), they took this on. That’s how I got to do my first trailer. I actually approached them to see if they wanted to distribute my first movie, and they saw the movie and didn’t want to take it on but they said, “Do you want to do some editing, do you want to make a trailer?” And I said great, and it worked out okay. It wasn’t a big triumph, it wasn’t a big challenge, but then the big challenge came.

There was a film that was very hard to do a trailer for, to compress it and give it a rhythm and make it exciting for people, and that was Wild Strawberries, but I did it. And they were so grateful, they said now you have all our work. And I did a Bergman film whose original title was The Face and they called it The Magician. I don’t know that it was one of his great movies, but actually the best compliment I ever got in my entire life was on a film that Bergman made that defied you. It was a film that dared you to make a trailer, and that was Through a Glass Darkly. In fact, they didn’t make a trailer in Sweden, they made a little 30-minute making of, and it showed them going to this island, the actors carried the lights, and it kind of a family affair because you really couldn’t sell this, but I did. Word got back to me that Ingmar Bergman saw the trailer and liked it very much, and that’s never been duplicated in my life. Then Janus got Jules and Jim which I did. L’Avventura, I think, was the easiest. It had fabulous main title music, and that saved my life. I just went back to see it at Film Forum. People have said that physically handling these classic and great movies, that by osmosis I absorbed something, and I think osmosis is a very good, very delicate way of saying you’re a crafty plagiarist.

Did your skill as an editor help you when directing films yourself, already having the knowledge of how to create a rhythm and tone to shape a picture?

If you want to be a writer, it’s learning English so that you have the skill of expressing yourself. Maybe you don’t want to use proper English, but that’s your choice, at least you know what proper English is and you know the grammar of filmmaking, you know how something goes together. There are certain rules in putting a film together so that it’s clear to the audience what’s happened–screen directions and so forth–and if you come from an editing room, you’re never intimidated by the rules of filmmaking and that’s a big, big plus. Particularly, if you don’t feel overly confident in your other skills, but if you have the skills of grammar so to speak, it’s a freedom, a freedom that I was very grateful for. I said this the night of Score, but I never came to film like a lot of people as writers. A lot of the great directors were writers, like John Huston. I’m not comparing myself to John Huston, but I brought a film technique. Unfortunately, it made me very dependent on other people’s structures, that’s why I went to the classics to get stories. I didn’t have the confidence to create a story. I knew the rules of filmmaking but I didn’t know the rules of dramatic structure.

Much of your work is adapted from literature, which is interesting in the context of pornographic films because it allows for them to already have a base that isn’t just purely sex. And whether it’s the hardcore films like Misty Beethoven or something much more demure like Therese and Isabelle, it’s everything in between the sex that allows the film to stand apart.

It’s funny you should use that phrase, that’s a significant one: the in-between. You know, you like to feel that what you do is filling a need, and if you’re not dealing with the in-betweens, nobody really needs you because anybody can really do that. I heard a lecture by an instrumentalist who said that it’s not what you play on the notes, it’s what you do in the silences. I always remembered that. It’s the in between that counts. Particularly when we’d do the Henry Paris films and people would say, oh it’s just a bunch of sex, and so you give them the sex and you’re successful. But it’s funny because across the street from where we were playing there was always a sexier movie with more sex. So why did people come to us, why did they see ours? It’s not just giving them a bunch of sex, it’s the in-betweens.

If you look carefully at Misty Beethoven you can see about six quarts of my blood. It was a complicated film.

How so?

That was the third one I did, and it kind of got away from me. We had the funds to do it and it just got bigger and bigger. It started out as a little film, but we wound up shooting in Manhattan, Deal, New Jersey, Kennedy Airport, Italy, Paris, and then we built sets in a studio on 106th. I’m glad it all fell together. I have a thing about saying to people how hard my job was, or how difficult something was, because once I hear people say that, there’s something wrong. Nobody wants to know that you worked hard, that’s what you get paid for, you should work hard. But it was a lot of stress because suddenly we had a lot of extras and we had a big advantage. Something you can’t plan, is that we were there at the apex of what came to be known as porno chic.

It made things a little easier, and you didn’t have the stigma of doing a “dirty movie.” So that was a big plus. I did two after that quickly, but it was a crest and then drugs came in. We were really lucky in that hard drugs were really not known. And I’m not naive, I noticed in the evening the crew would maybe go off and smoke some weed, but the serious stuff was not around. I don’t think we could have done it if that were not true. After that, you had the John Holmes scandal on the west coast and home video, so things changed dramatically and we were just kind of at the right moment. Again, that’s life, and you can never really plan trends like that.

You began your career during a tumultuous time for sexual politics. Did you ever see your work as a way to express your feelings on what was happening in society, or did you come into erotic cinema from another angle.

We were small, which is a polite way of saying we really didn’t have much money. So the only way you could attract an audience was by spending money and advertising. If you advertised, people would notice you, but we couldn’t do that, we had to use other means. There’s a fork in the road and you take one of those two forks: one of them is horror movies and the other is eroticism. For better or worse, I followed the erotic because I had this small distribution company and the first film I made, Dark Odyssey, was one of these films from the heart. It was dripping with sincerity and it was a disaster. Reviews were wonderful and it was very flattering, the New York Times said the perfect things you want to hear, but no one showed up. So I bought a French film that had, if I can be so vulgar, a woman’s bare breasts–Deep Throat was nothing compared to that period with a woman’s bare breasts, and not even in a sexual situation! So I bought that film and dubbed it and used all the skills I had as an editor, and suddenly doors opened and exhibitors would play the film and nobody walked out on it, like they did my heart-felt movie. So I continued along that line. I don’t know what else was going on in my psyche.

Maybe it was the fact that I grew up in a very restricted time. There was a phrase that Richard Pryor used–I guess we were the same age–he said that he grew up in “the great pussy drought of the 1950s.” It was a time of great, great restriction and not much interplay between the sexes. However, something I was fanatical about was that a lot of people used a sex film as a way of meeting women and a way of raising money, and I was obsessed about not falling into that. I thought, once you get that reputation you’re no going to get good people to work for you, and getting the good people I got, that was number one for me. I was very ego-involved with my work. My work was me, and if the work didn’t succeed, I didn’t succeed and if the work was bad, I was bad. That was more important than socializing. But anyway, we followed the path of eroticism.

If someone were asking me what they should do if they were starting out their career, I think I might advise them to follow horror films. They have a wider fan base and they have a lot of publications. Lynn Lowry was in everybody’s first movie, and now she still has a fan base that’s incredible. When she goes to conventions, Score is now important, but for most of her life it was the fact that she was in George Romero’s first movie and everybody’s first movie.

You take things are were deemed “taboo” and expose them in such a way where those “illicit” acts are merely a part of life. Coming from a time that was much more buttoned up and restricted, I love that your films present sex and sexual exploration in a way that is acceptable and meant to be pleasurable and enjoyed. There’s no judgement or condemning for indulging your sexuality.

You said it better than I could, that was the point of it all. It was sex without punishment, because when I grew up, all sex had to be punished. And if you enjoyed it, it had to be really punished or something terrible had to happen to you.

When it came to casting, you used both adult actors and European actors whom you already admired. How did you go about approaching who would be in your films?

Adult actors, that was a core. They were a little army here, and so in a way, it made life easy. It was divided into two camps: actors who did explicit sex and explicit sex people who acted. I was able to draw upon both and there’s no way I could have done that without actors. There were enough that they could play that stuff and make it work. In Europe, they read the script and I said this is what we’re doing and they, I don’t know, felt my enthusiasm, and for whatever reason agreed.

How was it to work with Jamie Gillis?

I had seen him off-Broadway before I went into porno. He was very good. He was an actor and very good. I picked up what he needed and he could play the stuff. A lot of the stuff was written for him because I knew, so to speak. He was a pleasure.

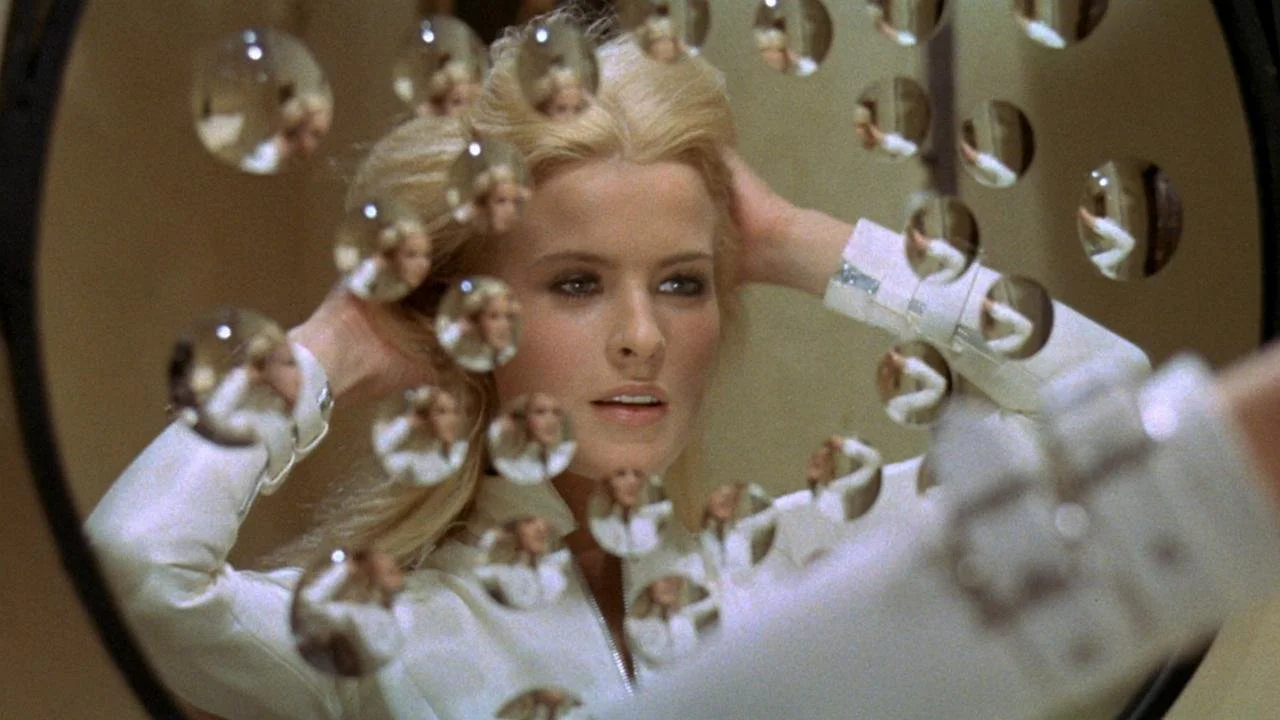

The production design of your films is always incredible, especially when looking to films like The Lickerish Quartet and the castle you shot in, and the whole world of Camille 2000.

He was a quasi-genius, Enrico Sabbatini. He did Camille and Lickerish Quartet, and I can honestly say the films would not be half of what they were without him. What happens, sometimes you just work well with people. Maybe it’s like some enchanted evening across a crowded room you see somebody–it’s similar to that. I guess you’re on the same wavelength, you’re on the same page, and I was very lucky to find him. Of course he was very gifted; Sophia Loren, she didn’t make a movie without him. He was very successful.

You’ve mentioned Alain Resnais as a filmmaker who was very important to you. What was it about his work that spoke to you?

Well, I was overcome by Hiroshima mon amour and I had never seen a nonlinear story before. It was like someone sitting on my chest got up, and it’s a freedom. It allowed me to explore the boundaries of film, of storytelling, and I was very grateful to him for that.

I've read that you said in making these films of films, it’s better to have the characters be of a wealthier class, or to have the film establish them as members of high society. Is that a way to relieve the viewer of being concerned with the logistics of their day to day lives and just focus on the narrative?

Well, that goes back to City College here in New York. I got my Bachelor’s degree there and the drama teacher said that if you’re doing a comedy, you don’t want people distracted, wondering how these people make a living. You want them to focus on the comedy and the plot points. I didn’t have to stretch too much. In Score he’s a photographer, but they never talk about making a living.

When you first started gaining an audience, who were the people who were coming to see your films? And as time went on, were you consciously trying to appeal to that demographic?

I guess it’s probably an alloy, a little bit of both. You get a basic erotic audience if it’s well done and there are pretty people, but the core audience we had, we called them “Young Moderns,” people that had been married about eight or nine years. At this period they were kind of a discriminating audience, and educated, and I think fairly well-to-do. That was the core of people that we got. I guess I felt at home with them and I was able to appeal to them in a sense. I did jokes that I knew they would understand.

Why did you decide to make the transition into the hardcore Henry Paris films?

To be really honest, I didn’t. All I did was the same as I was doing, I just carried the sex scenes a little further, but the kind of stories I told and the kind of humor, it was all the same. People say, “How did you change?” which is really complimentary, but I really don’t deserve it because I didn’t know how to do anything else. All I knew how to do was the kind of thing that I did. The humor and the storytelling in Score, the humor in Pamela Mann, it’s all the same, it’s just what I knew how to do. I was also very lucky to get the cameraman who did all the Henry Paris films. He was really very adept and very gifted.

Was it important for you to do something new with each film and not repeat yourself? Adapting vastly different works of literature is certainly conducive to that.

My first obligation was to me, I had to keep it interesting and exciting for me. That’s why everything I did, most anything I did next was very different. I had one horror image, and that was, been there done that–that kind of boredom that I felt seeps into filmmakers when they’re at something too long. So I tried to avoid that by changing subject matter, whether they were good, bad, or indifferent, they were different. If there is an excitement and there is a spark, that was one of the ways I kept it up.

That rack focus orgasm with the flower in Camille 2000 was gorgeously done, I loved it. Was that something that was always in the script or did that come from being on set and inside the world of the film?

The cameraman didn’t want to do it. He said, “I’m not sure exactly what you want, so why don’t you do it?” So I said fine, and I breathed alongside the actress. I almost fainted because I was hyperventilating, it was all that oxygen and I almost collapsed. The scene had a little bit of premeditation because we had to get a special lens from London to do that, for the focus.

But your DPs were always very important to you.

Directors of photography loved me because I gave them time and most people don’t have time, particularly independent films, but I stole the time so that they could do their job.

The Cat and the Canary came right after your series of Henry Paris films and could not be more anathema to them. Were you looking to take a breath of fresh air from that period of work?

Yes. It was too intense. In 23 months I made eight films, that’s four explicit and then additional footage to make it non-explicit so you could show it in other countries, so it was really like eight movies. It was very intense and I just wanted something different, and boy, I found it. Cat and Canary had been made five or six times before me and I was very lucky to get the cast I got. We were fighting the clock.

Lastly, how has it been to revisit your work in this context and have to speak about them after all this time has passed?

Well, I don’t watch the films so it’s very flattering the fact that people looked at the films because when they first came out they would look at the sex, the critics would look at the boss they should be writing for and what’s their position on censorship and now I think it’s nice that the focus is on the material, whether you like it or not at least you’re seeing what it is.